Issue # 4 Hanae Utamura

Curated by: Virginia Inés Vergara

In early spring of 2011, the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami hit Japan. At the time Utamura was planning on traveling from London, where she was participating in a residency, to Finland. She was born and raised 80 miles away from the site of the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear plant, and her home town was affected both by the tsunami and the resulting meltdown. As the scale of the disaster became apparent, she decided to return home to witness the devastation for herself, and to assist in the relief efforts by delivering food.

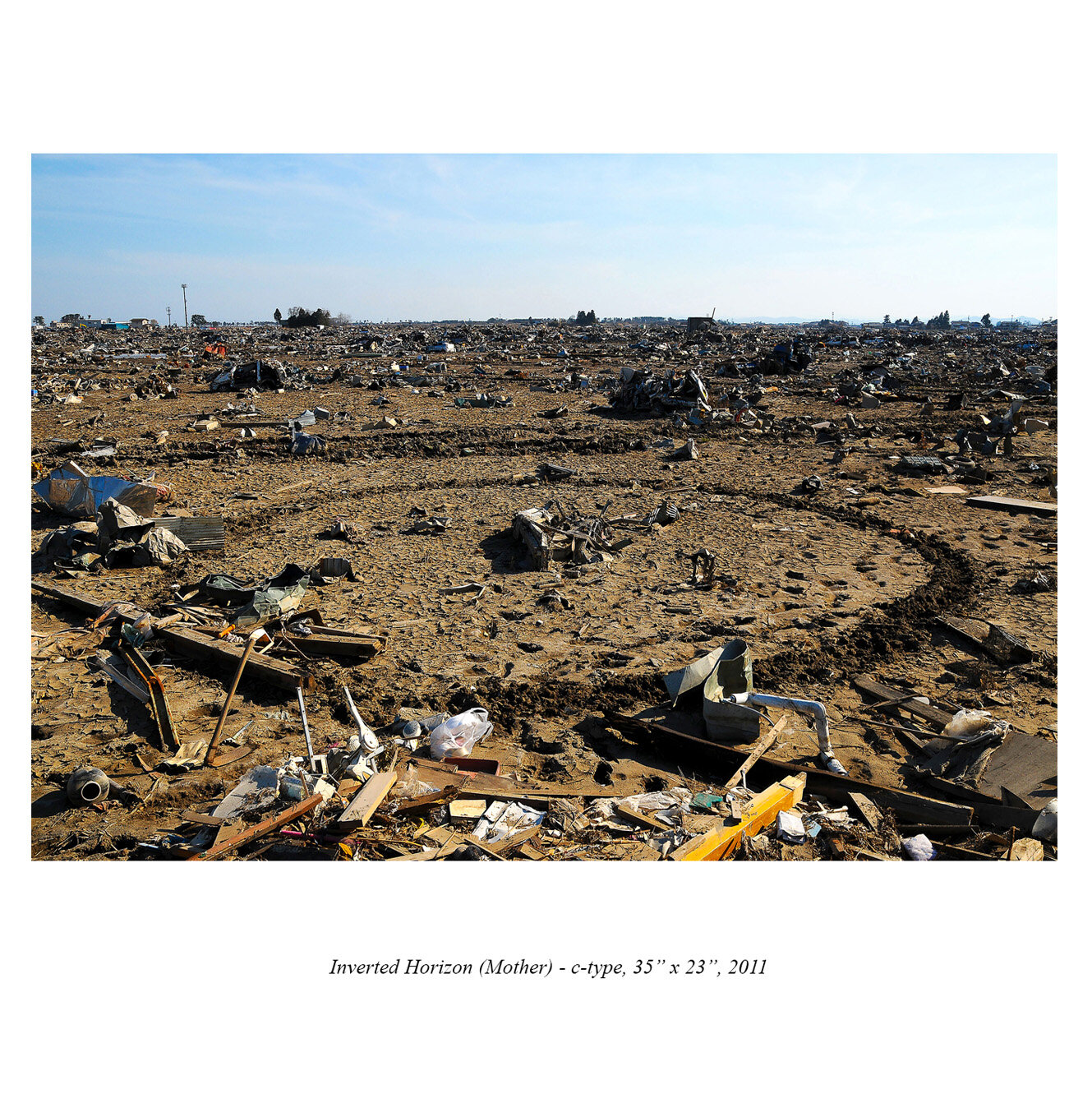

The daytime photograph titled ‘Inverted Horizon (Mother)’ took place in the ruins of a rice farm in Natori City. Utamura took a piece of rope and a hoe found on the site and tethered herself to her mother, almost like an umbilical cord. Her mother stood in what would be the center of the circle and Utamura used the hoe to excavate a perfect circle in the salted, lifeless earth. After completing the circle, the hoe was left where it was found and appears in the foreground of the photograph. This act commemorates the land and the survivors, and mourns the loss of farming as a way of life.

Prior to her return, an aerial image of the tsunami sweeping the farmland from the sea played repeatedly on television and computer screens. It left behind a seemingly infinite, barren landscape in Tohoku; farm land that had been rendered infertile by the saltwater of the tsunami. It was covered in debris, the oxidized possessions of the former residents of this area, tools used for farming and personal items. Humans were absent. Moved, she decided to visit with her mother the site of this image, the coastal rice farms in Natori city, Miyagi Prefecture, and in Rikuzentakata city in Iwate Prefecture which had been destroyed by the tsunami, and which resulted in a series of photographs of earth works titled ‘Inverted Horizon’ .

Utamura took the other two photographs titled ‘Inverted Horizon (Ground Zero)’ just after dusk, just as the last light from the sun vanished. To safeguard against future tsunamis, a 41 foot wall was erected and Rikuzentakata city was buried underground with soil, raising its elevation. The city became a lost landscape, and many of the victims of the tsunami were never found. Many of the victim’s relatives feel that the memory and the remains of their relatives are buried there, underground.

She drew a circle with slaked lime, which radiates brightly in the blue light. The way the slaked lime is spread is shaped by the wind from the seashore, the same sea that brought the tsunami. Utamura, who used this technique in all the works in this series, drew the slaked lime circle by tethering herself to her mother, who stood at the circle center. Lime traditionally plays several roles relating to life and death: it is used as a fertilizer to speed the growth of crops, and it is sometimes thrown on the bodies of the dead to assist with decomposition. Soil is essential for the cycle of life, it both takes our dead and nourishes us by providing our food. The circle symbolizes this continuum. Thus this work situates itself somewhere between grief and hope, as well as representing the cycle of life; its emergence, its decay, its decomposition. For even after an environmental tragedy, life, when left on its own, finds a way to take root and recover, like in Fukushima or Chernobyl, where trees, insects, and animals have managed to thrive in the 'toxic land'.

Unlike her previous earth-works, Utamura chose not to put her body in the photographs, her absence portraying the residents who disappeared from that land. Her digging is an act of cultivation, a way that humans have connected to the Earth since the dawn of agriculture. It is a way not only of maintaining our lives on Earth but also a moment of listening to the voice of nature.

Utamura and I reconnected in early March, in NYC, a few days before the WHO declared covid-19 a global pandemic and NYC became the new epicenter of the tragedy. The feeling of apprehension was palpable. That was the last time we saw each other in person but we continued contact through digital communication. I had a great desire to hear about her work, and how she was coping. She generously spent three afternoons explaining past artworks and projects as we talked about our personal situations. Utamura grieved after Fukushima. She was not directly affected, no close friends or family members passed in the catastrophe, but she saw areas once so familiar rendered unrecognizable and inhabitants she had seen in passing disappeared. As I write this I too have not been directly affected. But I find myself in a constant state of shock and shame at what is happening to those around me. I tried to put this in perspective by listening to Utamura's experience in the aftermath of Tohoku and making the "Inverted Horizon" series, which felt more impactful and relevant each day as the covid-19 crisis deepened.

The most striking images of the pandemic, especially in its early stages, were normally crowded cities without any people. The most famous image before the virus reached New York City was in Venice, where the most crowded squares in the world were left empty. Much like in Utamura's images, the absence of humans signified loss.

The fact that she dropped everything in the aftermath of the Tsunami and went home, is a very human impulse in response to a tragedy. I did the same thing on 9/11, returning to New York City from Rhode Island. You wanted to see how the city was, how things were going on, how your home had been affected and how your loved ones were coping. It has been almost impossible to satisfy this impulse during the pandemic. I have not yet seen or walked around so many of the places that I took for granted for so many years. I don't know what most of the city looks like even though I am living in it still. It is the same with my family and friends, as safety dictates that we remain apart until the danger passes. I judge the health of the city from indirect signs, like the frequency of ambulance sirens coming through my window. We are all here but we are disconnected.

People need a body to mourn. Eventually, the Japanese government exhumed the buried remains of Natori and Rikuzentakata and tested them for human DNA to provide closure for the families of the deceased. But how do you mourn when the tragedy is happening around you, in real time? No one talks about this, yet covid-19 compounds our grief further by preventing us from mourning. Because covid-19 spreads so easily and is so deadly, we must remain distanced from our family and friends, those with whom we share our grief and rely on for support. Funerals are too dangerous, and the bodies of the dead must be cremated, preventing us from saying goodbye. In the ICUs of the hospitals, victims suffer alone in quarantine, and final goodbyes are said over face-time, if at all. Our grief goes unacknowledged, building up every day.

Seeing Utamura’s piece and discussing it with her was different because of the pandemic. It helped me understand and contextualize what was happening around me and what I was feeling, and it also helped me understand what Hanae felt in the aftermath of the tsunami. One thing that has been missing but which is readily apparent in Hanae's work is hope and recovery. Tohoku has been recovering since 2011, and we, too, will eventually recover.

Curated by: Virginia Inés Vergara

Hanae Utamura is a Japanese interdisciplinary artist based in between NYC and Buffalo, NY. Utamura works in video, performance, new media installation, and sculpture. She connects human beings and earth, using body as a vessel. The negotiation between nature and civilization, and how the will of life manifests itself in its processes has been the central focus of her practice. She reflects our relationship to nature, focusing on how we imagine, experience, and affect the natural world through scientific development through historical narration.

Hanae Utamura is a Japanese interdisciplinary artist based in between NYC and Buffalo, NY. She received her masters degree in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Art and Design and bachelor degree in Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. Utamura has received support through numerous international residencies and fellowships including Akademie Schloss Solitude (Stuttgard, Germany), Künstlerhaus Bethanien (Berlin), PACT Zollverein(Essen, Germany), Art Omi (Hudson, U.S.), Santa Fe Art Institute Residency, AomoriContemporary Art Center (Japan), National Museum of Contemporary Art, Changdong ArtStudio (Seoul, S.Korea), Seoul Art Space_GEUMCHEON (Seoul, S.Korea), Florence Trust(London, U.K.) and more. She has been awarded NYFA Immigrant Artist MentoringProgram, Shiseido Art Egg Award, Grant program by the Japanese Ministry of Culture, the Pola Art Foundation, UNESCO-Aschberg Bursary Award, and Axis/Florence Trust Award. And has been exhibited extensively in Asia, Europe and U.S.She was a visiting scholar at New York University in 2019, supported by Japanese Ministry of Culture, Japanese government as a part of Japan - United States Exchange Friendship Program in the Art.