Issue # 30 Juan Dávila

In conversation with Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán: You're well-known for your pictorial oeuvre, but you have always had an interest in exploring and intervening posters. Is it the agility of the medium that attracts you?

Juan Dávila: What always attracted me in posters is their wit and extraordinary designs. I have always loved the posters of Leonetto Cappiello, more than my great aunt's David Hockneys— “high art”. We have in the everyday life of popular culture the great aesthetic pleasure of the poster. It is not an incorporation of high culture into a less considered form of citizens’ domain, which has other aesthetic sensibilities. High art does not care for the continuity of art and life since it would imply the subordination of the art form to function.

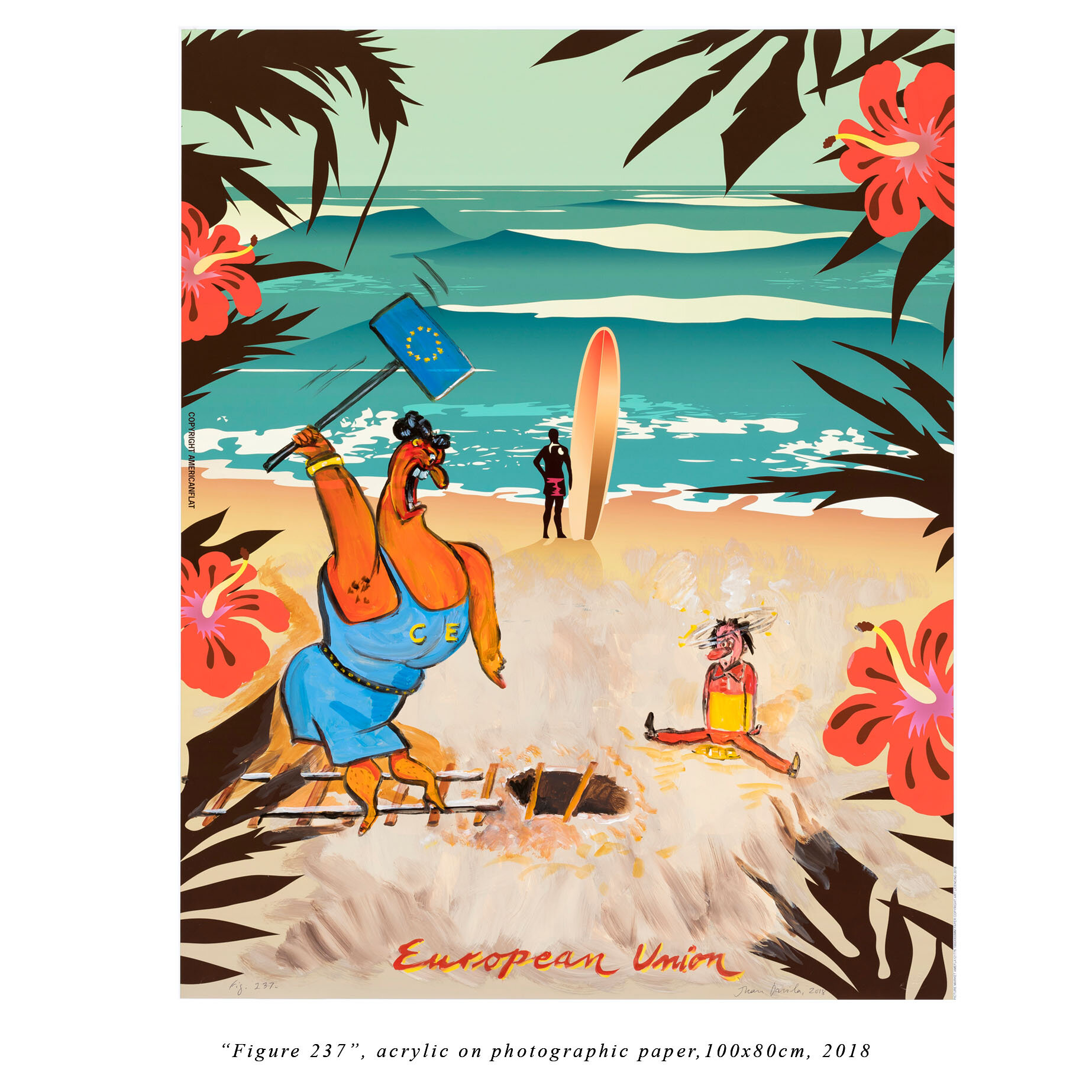

What attracts me is not the agility of the medium but its ambivalence of meaning. They sell products or services, but equally posters place us between culture and class, psychic realm and social life. Not to mention their undercurrents of race, sexuality. Posters arouse something in us excluded from museums, humor for example.

Paco: How would you say is the relationship between these two media? Is the poster a kind of quick sketch of an idea that you don't necessarily want to end up developing into a painting?

Juan: I use posters as a readymade background, a resolved background for placing figures. I can alter them without laboring too much. I aim to reveal an undercurrent of other meaning. It is not testing a sketch for a future painting, but an alteration of desire from what the poster promises us. A beautiful slide between spheres.

Paco: Indeed, a different level of alteration or intervention is visible in the different posters that allow you to address topics that have been a recurrent leitmotiv in your work since the ‘70s: gender, identity, the troubled relationship between Spain/Europe and Latin American, the role of the church, just to mention a few, that were characterized among others in the flamenco dancer, the bull fighter, the surfer and the Pope. The medium is different, but the conceptual scope is the same.

Juan: It is true that an artist has some repeating subjects that curators might consider essential in his work. They are not chosen rationally and any explanation the artist might give is a sort of self-censorship. The current art industry demands clear explanations, and everything must be ticked OK. If you ask a person what’s your personality, or even worse, what is your mental structure, you get an empty look. It’s a bit like knowing if we smell good or not, we don’t know. In art we might know later on, but with regards to desire most of it has been repressed or foreclosed.

I have been labelled pornographer, gay, Latino, different, scandalous, political, etc. but it is not me. Labels are just commonplace at work. I particularly dislike the psycho-social fashion of looking at art. What you need to know is in the object itself, and it is much more than the mere price tag. Regarding the different subjects in my work, I can only say that it is not a conscious project. I paint what comes to me in the moment and it is in all mediums like that: an unknown ‘something’ that repeats.

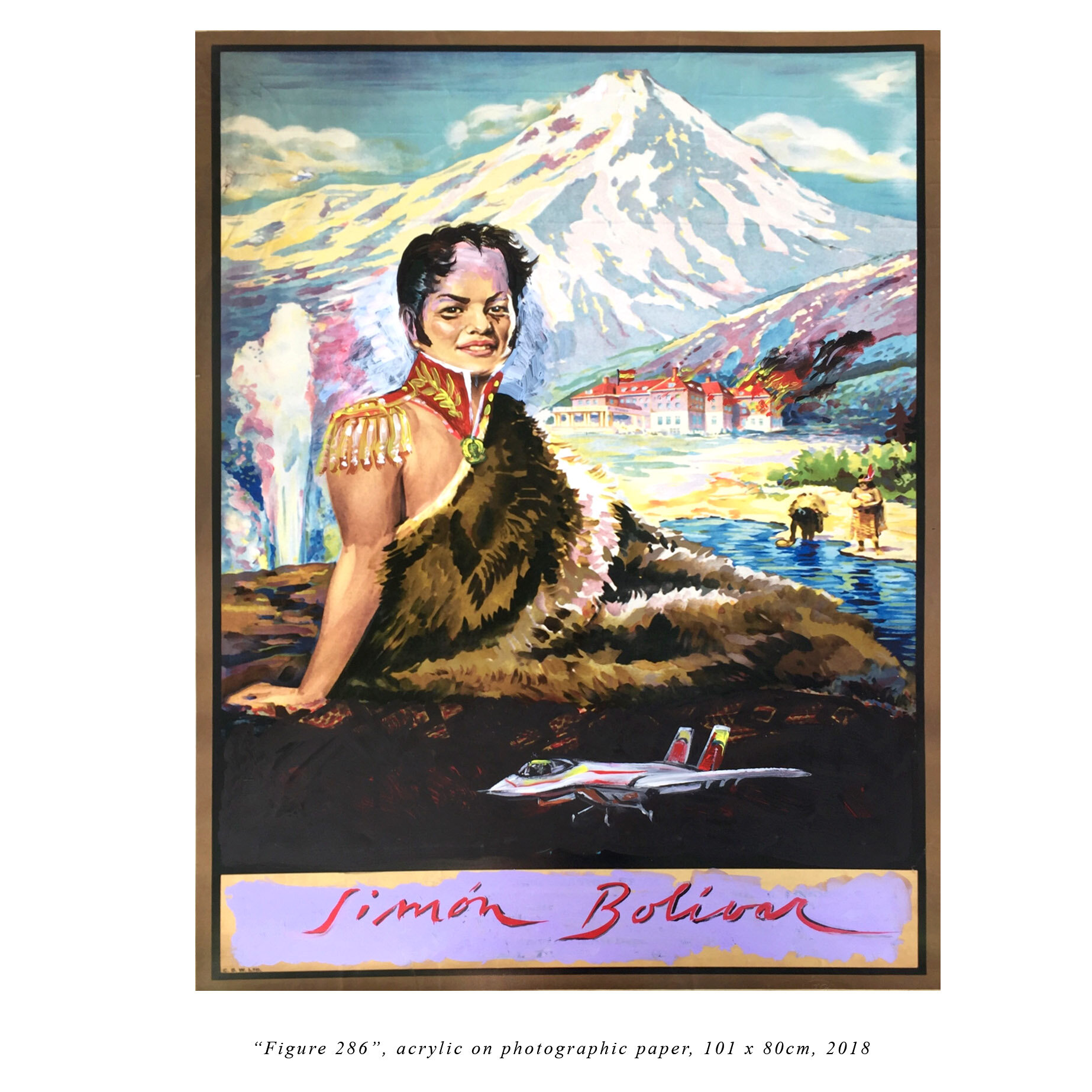

Paco: You made a new poster of Simón Bolívar, who looks very exotic and effeminate at the same time, and hardly like a Latin American historical macho hero. Is Simón Bolívar with his flaws and his virtues the personification of the convoluted reality that Latin America stands for? Can you explain to us your attraction to the figure of Bolívar?

Juan: I have altered the posters you mentioned twice. In one I transform an indigenous New Zealand woman into a Chilean Mapuche, in the other she becomes Simón Bolívar. I use his image as the Father symbol of Latin America. He is not the macho warrior we are meant to love for liberating Latin America from the Spanish conquerors. He is a half-caste, if one is allowed to use that word now, son of a woman of color. He is known as a womanizer, 500 hundred conquests per month I believe, a small-sized dandy in great uniforms and so on. To me this is feminine, needing to prove the contrary, despite his great merits.

I am concerned with the symbol he became, not the person. Latin America is “machista” and white, and yet I feel that they are “mestizo” countries in reality. Bolívar allowed the criollos to rule and they imitated the Spanish class system. By contrast I depicted an indigenous Mapuche woman in front of her ancestral land, today stolen by several Chilean governments in order to give them to the forestry industry. Mapuches are still persecuted. Put the two posters together and you have the blending of psychosis and hybridism, the eternal split there.

Paco: Is this interest for the poster something than can be related to your early interest in Chilean magazines like Ecran, Topaze and characters like Verdeja?

Juan: The posters appeared at the beginning of the 19th century, allegedly with Jules Cheret as the inventor. Of course, I was interested in them ever since. It was used for promoting goods and services, later on movies, political propaganda and today for horribly decorating offices looking like homes. It was always the poor cousin of the arts consigned to ‘design’. In fact, their aesthetic is superb, superior to museum’s art at the time. The use of them outdoors has become obsolete since capitalism’s surveillance of the internet. So, my love of magazines like Ecran, Topaze, Condorito, Rico Tipo was formative alongside with the posters. Van Dyck’s paintings could not compare with the faces in their covers. I have never looked back.

Paco: Finally, you also published recently a small sketch book titled 365 in which you also tackle some of these topics that are recurrent in your practice. Some of these sketches have materialized in paintings.

Juan: The book 365 was printed by Taller Gronefot in Santiago de Chile and it was edited by Jorge Gronemeyer and Andrés Durán in 2020, while the drawings were made in 2018. It has been described as a sketch book of ideas for paintings. In fact, I think that the line drawings, done in less than a minute, have another scope: a way to catch a fleeting thought. The eloquent line has something that is mysterious, nothing to do with a practical purpose. The spaces, references, figures become alive in a space that we cannot recognize exactly. They appeal to a visual recognition without words. The art and historical references are there but not as an art and politics program. They appeal to the imagination which is sorely lacking in this era of political art bureaucrats and their controversy for tourism and money.

Images Courtesy of Juan Dávila/Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne

The conversation was conducted in English.

Juan Dávila was born in Santiago de Chile in 1946. In 1974 he moved to Australia. He works and lives ever since in Melbourne. Dávila studied both Law (1965-1969) and Fine Arts (1970-1972) at the University of Chile. A prolific artist, he participated among others at the Sao Paulo Biennale in 1998 and documenta 12 at Kassel in 2007. Dávila is also editor of the Art and Criticism Monograph Series in Melbourne. He started to exhibit in the early 70s both in group and solo exhibitions. A selection of his solo exhibitions include Juan Dávila (1974) at Galería CAL (Coordinación Artística Latinoamericana), Santiago de Chile; Fable of Australian Painting (1983) at the Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne; Pietà (1984) at the Performance Space, Sydney; Picasso Theft (1986), Avago Gallery, University of Sydney; Mexicanismo (1991) at the Bellas Gallery, Brisbane; Juanito Laguna (1994)at the Chisenhale Gallery, London; Rota (1996) at Gabriela Mistral, Santiago de Chile; Verdeja (1998) at ARCO98 Madrid, Greenaway Art Gallery; Love’s Progress(2000) at Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne Art Fair; Juan Dávila: Works 1988-2002 (2002) at the Australian National University Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra; Juan Dávila Retrospective (2006) at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney and the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; The Moral Meaning of Wilderness (2011) at Griffith University Art Gallery, Brisbane and the Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne; Juan Dávila: Imagen residual (2016) at Matucana 100, Santiago de Chile; and Juan Dávila: Pintura y ambigüedad (2018), Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Castilla y León MUSAC, León. Among his group shows are included participations at Exposición Anual (1972) at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago de Chile; Six Approximations to Surrealism in Chile (1975) at the Chilean-French Institute of Culture, Santiago de Chile; Spectres of Our Time(1981) at the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Artist’s Proof: Leppe, Cárdenas, Dávila at the XII Biennale of Paris, Museum of Modern Art, Paris;Australian Perspecta (1983) at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; From Another Continent: Australia, the Dream and the Real (1983), Museo of Modern Art, Paris; Private Symbol: Social Metaphor (1984) at the 5th Biennale of Sydney, Sydney; Isolaustralia (1985) at the Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation, Venice; Stories of Australian Art (1988) at the Commonwealth Institute, London; Prospect 89 (1989) at the Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt; Transcontinental: 9 Artists from Latinamerica (1990) at the Cornerhouse Gallery, Manchester and the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham; El desafío a la colonización (1991) at the 4th Biennale of Havana, Havana; America: Bride of the Sun (1992), Royal Fine Arts Museum, Antwerp; Cartographies (1993) at the Winnipeg art Gallery, Winnipeg and the Biblioteca Luis Arango, Bogota; Cocido y crudo (1994) at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid; Intolerance (1996) at the Banff Centre for the Arts, Banff; 1a Bienal de Artes Visuales del Mercosur (1997), Porto Alegre; A sangre y fuego (1999) at Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castello (EACC), Castellón; MCA Unpacked II (2003), Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney; Arte Contemporáneo Chile: Desde el Otro Sitio/Lugar (2006), National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul and Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Santiago de Chile; Andy and Oz: Parallel Visions (2007), The Andy Warhol Museums, Pittsburgh; Cubism & Australian Art (2009), Heide Art Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne; Perder la forma humana: una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (2012), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS), Madrid; Juan Dávila: Hysterical Tears (2015), Institute of Modern Art (IMA), Brisbane; Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art-APT8 (2015-16) at the Queenlands Art Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), Brisbane; A decolonial geographic (2017) at Devonport Regional Gallery, Devonport; EVA International, Ireland’s Biennial (2018), Limerick; Intimacy, Activism and AIDS (2018), Tate Modern, London; The Abyss: Strategies in Contemporary Art (2019) at Griffith University Gallery, Brisbane.

The solo exhibition Juan Dávila: Social Contract (Chilean Trilogy), initially scheduled for 2019 at Matucana 100, will be held in 2022.

PACO BARRAGÁN has an international PhD from the University of Salamanca with a residency at the Alvar Aalto University in Helsinki. He was awarded the Extraordinary PhD Award of the year 2020 of the University of Salamanca for his doctoral thesis “Narrativity as Discourse, Credibility as Condition: Art, Politics and Media Now.” Barragán is Contributing Editor of Artpulse magazine. He was the artistic director and curator of CIRCA Puerto Rico and PhotoMiami art fairs between 2004-2007, after which he authored in 2008 The Art Fair Age (CHARTA). He was co-curator of the Prague Biennale at the National Gallery (2005), la Bienal de Lanzarote (2008) and Toronto’s Nuit Blanche (2016). Barragán was also the International Communications Director of the Bienal de Valencia (2003). He was the artistic director of the Castellón International Expanded Painting Prize (2004-07) and of the first edition of the International Festival SOS 4.8 in Murcia (2009). A prolific curator, Barragán has conceived 91 international exhibitions among which Don’t Call it Performance at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (2003), ¡Patria o Libertad! On Patriotism, Nationalism and Populism at COBRA Museum (2010), Erwin Olaf: The Empire of Illusion at MACRO-Castagnino (2015), and Juan Dávila: Social Contract (Chilean Trilogy) at Matucana 100 (2022).